Photo by American Public Power Association on Unsplash

Powering Distributed Computing On Renewable Energy

Lessons from Bitcoin

Table of contents

- 1. Electricity grid instability: the blindspot in carbon-aware computing

- 2. Renewable energy fluctuations and the electricity grid

- 3. Green computing as grid stabilisation tool: Bitcoin's Proof of Concept

- 4. Pitfalls of carbon aware computing at scale: lessons from Bitcoin

- 5. Renewable electricity supply chains: blindspot of the green transition

- 6. Conclusion

1. Electricity grid instability: the blindspot in carbon-aware computing

There is a lot of ongoing work in exploring ways to tie computing jobs to the times and places in the world where the electricity supply runs mostly on renewable energy. This is known as carbon-aware or carbon-responsive computing. But they tend to be extremely niche and small-scale with some notable exceptions I hope to cover in a later article.

There is however a caveat, which is seldom accounted for in the literature and messaging around carbon aware computing: powering your computing on renewable energy is not necessarily enough to reduce its CO2 emissions.

Counter-intuitively, to balance supply and demand, many national grids replace each additional unit of electricity demand from renewable sources with coal and natural gas equivalents. As a recent White House report on the Climate and Energy Implications of Crypto-Assets in the United States summarises it:

As the amount of renewable sources is held constant, but electricity demand increases, additional fossil power will likely be dispatched. This displacement results in no net change or in increases in total global emissions through a process called leakage.

So the renewable electricity consumed by your computing job, if it increases net electricity demand during "green hours" above the existing surplus energy, results in at least the same emissions as if it was powered by fossil fuels, since the grid will replace its additional energy demand with fossil fuels.

What's more, it is now understood that because of the leakage issue mentioned above, there is in fact not a one-to-one equivalence between fossil fuel energy and renewable energy emissions displacement, so you need extra renewable energy to displace the same amount of fossil fuel emissions. This means that swapping 1 terawatt of fossil fuel energy for 1 terawatt of renewable energy will not result in a 100% emissions displacement, so the like-for-like emissions of your "carbon-intelligent" computing job may still add up to net CO2 increases.

Consequently, there are only two ways to ensure that green computing powered by renewables would result in zero direct emissions on the main electricity grid:

Using only surplus renewable electricity that would otherwise be curtailed by the grid.

Constructing or contracting for new renewable electricity sources to power additional consumption from computing.

This is one key reason why within the field of carbon-aware computing research is underway on ways to target specifically stranded renewable energy, that is, energy that peaks when the sun decides to shine and clouds to part and winds to blow, at exactly the times when energy is not being consumed in sufficient volume by the grid. At those times the excess energy is not useable and could even lead to instability in the electricity grid, so it becomes curtailed and essentially thrown away and wasted. If we can target our computing jobs at that wasted renewable energy, we would help reduce digital emissions, stabilise the grid and avoid perverse effects from competing for a limited supply of available renewable energy with other users.

Most carbon-aware computing projects are cloud based, running their jobs on distributed cloud servers at times and places they happen to be powered by a preponderance of renewable energy in their respective electricity grids. Google in particular invested heavily in tracking the live energy mix across its global network of cloud servers and developing tools to predict and distribute its own computing jobs for minimal fossil fuel consumption. It then made those tools available to external users of its servers, enabling carbon computing at scale. It is not clear to me whether Google takes the emission displacement asymmetries into account in any area where it does not produce its own electricity, or whether targeting renewable-powered servers is in fact resulting in fossil fuel emissions from grid compensation protocols.

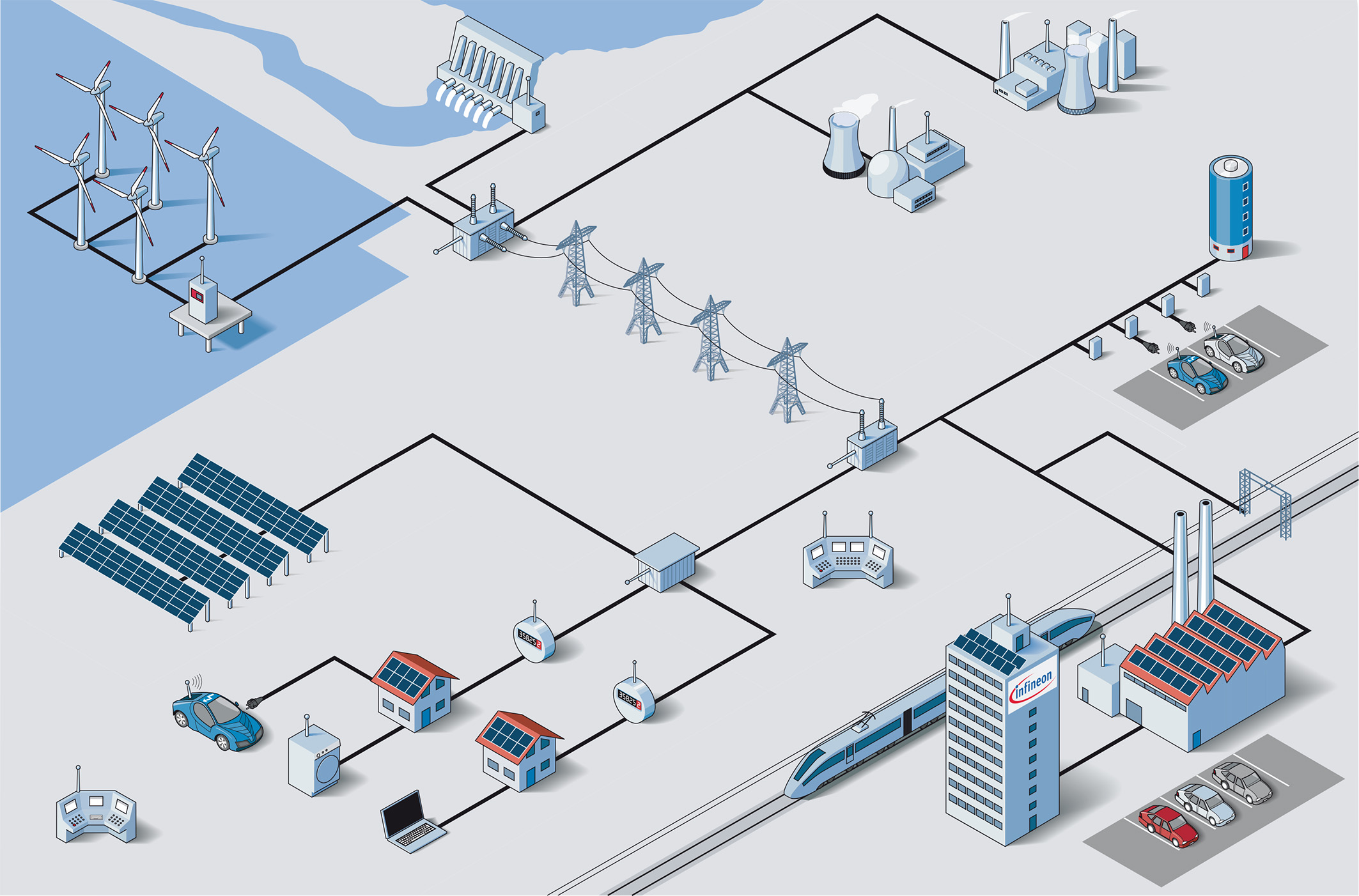

But this is not the only, or necessarily the best model for all use cases. An alternative, much less widely discussed model, is to directly co-locate one's servers with the renewable energy generation plants, and partner with electricity suppliers to use computing jobs to stabilise the grid. Bitcoin is at the cutting edge of this form of carbon-responsive computing, with several experiments at scale, and the green computing world would do well to learn from both its successes and its failures.

2. Renewable energy fluctuations and the electricity grid

To ensure the safe operation of the grid, voltage, frequency and similar electrical oscillations must be kept within specified ranges. This requires maintaining a constant balance of electricity supply and demand. If the balance is lost, blackouts, brownouts, and other grid disruptions can ensue. An increasing share of (unpredictably fluctuating) wind and solar energy in the electricity mix introduces unplanned peaks and drops. Whereas in legacy energy systems the amount of fossil fuel energy coming into the grid was under human control, and could therefore be stabilised on the supply side in a fully planned way. The more renewable energy is part of the mix, the more electricity generation (supply) is not under the control of humans and cannot adapt in a planned way to changes in electricity demand.

If every New Year's eve generates a predictable spike in electricity demand at night, under a fossil fuel-powered system, you simply "open the taps" and generate more electricity to meet demand and keep the grid on an even keel. In such a system, keeping demand and supply in balance is the job of the supply side, the people controlling the gas and coal electricity generators.

But in an electricity grid powered by solar and wind, you cannot simply will the wind or the sun to generate the planned energy spike at precisely 8 pm-2 am. In a grid powered by renewables, the only way to ensure that supply and demand are balanced is for electricity consumers to adapt to the rhythms of sun, water and wind. If consumers peak their demand when renewables are low, the grid could break. If renewables generate a sudden spike in supply when everyone is sleeping and companies are on holiday, that extra electricity will have to be dumped before it breaks the grid.

Clearly, it is hard to orchestrate an entire population to fit its rhythms to those of the natural elements, so electricity grid maintainers have created "demand response" programmes that pay companies to use electricity more intensely when consumer demand is not enough to spend the surplus renewable energy, and to stop all activity when consumer demand exceeds the available renewable electricity supply.

The more renewable energy powers the electricity grid as we advance in the energy transition, the more the need for demand-side stabilisation mechanisms.

3. Green computing as grid stabilisation tool: Bitcoin's Proof of Concept

Because computing can be electricity-intensive, because it can be located anywhere, and because it can be increased or diminished at will, it can be a great "load resource" for such demand response mechanisms, and Bitcoin has been the pioneer in harnessing this opportunity at scale as described in the previous post of this greening blockchains series.

I gave examples of grid participation schemes in Texas whereby Bitcoin miners are able to mine intensively (i.e. run intensive computing jobs) outside of peak times, and are paid by the tax-payer to stop mining/computing (and consuming electricity) when local grid demand is high. There are two types of such grid participation schemes around Bitcoin, reviewed in detail in a recent Masters' thesis:

Bitcoin miners acting as "load resources" in conventional demand response programs, enabling them to participate in day-ahead markets. This helps with electricity demand, but does not guarantee that the energy mix powering Bitcoin mining is renewable. This is the larger share in the Texas experiment.

Price-responsive Bitcoin mining, where miners are located behind-the-meter (BTM) directly at renewable power plants, mining when the market price for renewable electricity is low and refraining from mining when it is high. This green computing pattern is mostly based in West Texas, and this is the pattern that is most worthy of study by the wider green computing movement.

One crucial thing the Texas experience demonstrates is that with the right incentives, compute equipment can be co-located with renewable energy sources at scale, with miners flocking to Texas to carry out a gigantic amount of distributed computing powered exclusively by renewable energy. Close examination of the Texas model, introduced in my previous post, provides both some fantastic innovations to potentially emulate across distributed computing use cases, and also some extremely serious pitfalls to design for and avoid.

There is yet another complementary approach to carbon-aware computing that Bitcoin has made inroads on, and which have not been explored by the green computing movement. It involves linking distributed computing, such as Bitcoin's mining network, to the mostly off-grid, steadily growing distributed renewable power network (small-scale solar and wind generators in homes, offices, streets, fields and the like, and in some cases entire small-scale power plants).

The largest-scale experiment by far in using distributed electricity generation to power distributed computing was Bitcoin China between 2014-2021:

When the first group of bitcoin miners arrived in Sichuan around 2014, the sites they chose for bitcoin factories were near small hydropower stations that did not connect to the national power network... For the bitcoin miners, the power price of such offline stations is lower than the power price sold online... The arrival of the bitcoin factory ...made some small hydropower stations profitable.

At its peak, China dominated 75% of the global Bitcoin mining infrastructure, and in the summer months when rain is plentiful, most of this eye-watering amount of distributed computing was powered by these small renewable hydroelectric plants. China’s winters are arid however, and solar and wind farms don’t produce a steady enough supply to run mining operations around the clock, so miners often turned to coal to compensate, negating any environmental gains from the summer. This put China's trajectory toward Net Zero in danger, leading, together with grid load and economic issues, to the 2021 crackdown that finally stopped the majority of Bitcoin mining in China.

Another variation on the use of distributed renewable energy generation to power distributed computing focuses on harnessing the surplus energy of even smaller-scale alternative energy providers, with one evocative proposal to use domestic solar generators to power distributed volunteer computing being floated by Nurminen et al. Bitcoin mining has innovated in this area too, with one promising approach being the company Soluna, in Morocco, which is researching how to finance off-grid renewable energy projects with Bitcoin mining.

Soluna's example, where off-grid projects are too small and too remote to be connected to and sell energy to the electricity grid, they can monetise their local renewable power generation via Bitcoin mining as a way of financing capacity growth until they can integrate into the national power grid. This is an interesting model, where renewable energy powers profitable computing, which in turn finances renewable energy expansion, allowing for more profitable computing. This is a model that could be applied to potentially much more meaningful and societally useful computing than Bitcoin mining.

4. Pitfalls of carbon aware computing at scale: lessons from Bitcoin

I pointed earlier to a dangerous blindspot in carbon-aware computing advocates, relating to the fact that simply switching to renewable energy does not necessarily reduce emissions. Perhaps an even bigger blindspot in the literature and messaging is that there is almost no acknowledgement that renewable energy currently powers only 13% of our global primary energy needs, and stranded renewable energy represents a tiny fraction of that. If all current Bitcoin usage targeted surplus renewable energy, let alone if every use case for carbon-aware computing did the same, the likelihood of perverse effects is high.

An example of such perverse effects could be price inflation. There is evidence from Texas, New York and China that where Bitcoin mining scales up in a locality, local consumer electricity costs also rise, meaning tax payers pay for both, the demand-response subsidies, and a "Bitcoin tax" on their bills. This would apply to any electricity intensive compute that took its place.

Another example of preverse effects is the way Bitcoin's electricity demand, as we saw in Texas, can place the grid under strain, renewable energy or not, attracting regulatory attention from Congress. In China too, pressures on the electricity grid led to regulatory warnings and interventions in 2019 that prefigured the final crackdown in 2021. In Venezuela, where subsidised electricity and economic collapse made Bitcoin a financial safe haven, Bitcoin mining spikes led to grid failures and blackouts with 90% of the country being without electric power for several hours, and whole regions losing access to electricity for an entire week. The economic, social and human impact in a country without a functioning social net, was immense.

5. Renewable electricity supply chains: blindspot of the green transition

Solar, wind and hydroelectric energy are, for all intents and purposes, endlessly renewable. But turbines, photovoltaic panels, lithium batteries and similar machinery needed to turn renewable energy into usable electricity rely on the extraction of minerals and metals that are not only not renewable, but too scarce to meet projected energy demand.

Failure to account for this is a blind-spot that extends beyond green computing to the green tech movement as a whole.

The results show that proven reserves and, in specific cases, resources of several metals are insufficient to build a renewable energy system at the predicted level of global energy demand by 2050...

We show here that even if the energy system was fully renewable, supply constraints on several elements other than carbon would still compel us to reduce our energy demand.

Enough Metals? Resource Constraints to Supply a Fully Renewable Energy System

Green energy is technically much greener than fossil fuel energy and therefore a key tool in our battle against climate change, but at scale, it is not altogether renewable: it merely shifts the supply chain challenges from fossil fuels to minerals and metals.

This is still preferable, minerals and metals, unlike fossil fuels, allowing for recycling and substitution, reducing overall emissions and improving energy resilience. But it is not a magic formula that spares us from the need to reduce our energy consumption. This means that running computing on renewables does not render its energy voraciousness moot, even in an all-renewable utopia.

6. Conclusion

There is so much to learn from some of the applications Bitcoin has pioneered at scale in the area of renewable energy, grid demand management and stranded energy distributed computing. Bitcoin's absolute social utility is debatable, as I discussed in a previous post. But its relative social utility is clearer: there are surely many more socially beneficial applications of computing, and the models of greener distributed computing pioneered by Bitcoin could be harnessed for such applications too.

As an example, there is an ongoing project aimed at discovering causal relationships among human genes to improve drug repositioning. Instead of running on a single supercomputer, it is distributing the compute task across a huge network grid of small computers, and has itself raised the possibility of being able to power this network from distributed renewable power generation, although not yet taken steps to make it happen.

If projects such as these, or other volunteer distributed computing projects could be repurposed to run as demand response mechanisms, the benefits could be planetary.

The challenge is economically incentivising such uses, although there are initiatives already offering potential Proof of Concept in the blockchain space, such as Gridcoin, Curecoin and Foldingcoin. A recent review of similar "added-value" innovations has identified an expansive horizon beyond Bitcoin's trudging consensus algorithms.

Beyond blockchains, mapping the socially beneficial computing use cases that would be an equally good fit, technically and commercially, for distributed power generation and grid participation implementations of carbon responsive computing, is itself an area of research ripe for exploration, which I believe can yield truly transformative fruits.